The art of plastic surgery

Plastic surgery is a very creative field of medicine and many consider that it is an art. It is, perhaps a good example of where art meets science.

Aristotle is quoted as saying: ‘Art, indeed, consists in the conception of the result to be produced before its realisation in the material.’ This is an essential requisite for a Plastic Surgeon; it is the quality that distinguishes the artist from the technician.

Plastic Surgery is a very wide ranging specialty. It could be defined as the manipulation, repair and reconstruction of skin, soft tissue and bone. It is not restricted to one organ or tissue type. The emphasis is on maintaining or restoring form and function. Plastic surgeons often work in a team with other specialties (trouble shooting, innovating).

The word Plastic is derived from the Latin plasticus – molding, and the Greek plastikos – to form.

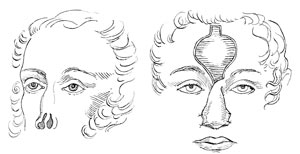

Plastic surgery had its origins in ancient history first relieving facial deformity, particularly nasal, resulting from war and punishment. The first recorded nasal reconstruction was described by Sushruta in the16 – 17th century BC. Gaspare Tagliacozzi in the 16th century could be said to have laid the corner stone of modern Plastic Surgery.

Indian Rhinoplasty –16/17th cent. BC - Sushruta

Gaspare Tagliacozzi (nasal reconstruction) –16th Century

It was not until the 19th century that some of these principles were applied to other areas of the body. Hand surgery only in the last century. Sir Harold Gillies is considered the founding father of British Plastic Surgery. He did extensive work, and made many technical advances during World War I.

Sir Harold Gillies – WWI

Australia has been at the forefront of recent advances. Dr Ian Taylor performed the first microvascular free tissue transfer in the 1970’s in Melbourne. Prof. Wayne Morrison is a leader in the exciting, emerging field of tissue engineering.

Cosmetic Surgery has evolved from reconstructive techniques over the past 60–70 years. A sound training in reconstructive plastic surgery along with an artistic sensitivity for contours and proportion is thus required for optimal results in cosmetic surgical procedures.

the concept of beauty

This is an important issue to both plastic surgeons and artists. It is based purely on our external appearance—the way we look.

What is considered beautiful changes with time and fashion and there are significant cultural differences; however the basics of beauty are universal across time, culture and race.

The view of beauty is influenced by instinct, social conditioning, a concept of transcendent or spiritual beauty and personal taste.

Many features we find attractive are also signs of fertility, youth and health. Sexual stereotypes are not strictly artificial.

The ideal female face has a clear complexion, childlike features with large eyes, full lips, small nose and chin, high set brows, prominent cheek bones, narrow cheeks, well defined jaw line and full, thick hair. The ideal male is similar, but has a thick flat brow and a larger jaw and nose. Symmetry is also a desirable feature.

This view of beauty is modified by social conditioning. The cosmetic, media and fashion industries thrive on our need to feel more beautiful.

Much early Western art was religious. Botticelli and da Vinci attempted to capture the beauty of the spirit. A spiritual ideal beyond the ordinary would imply truth, goodness and beauty.

Personal taste is superimposed on these factors.

As fickle and shallow as it may sound, studies have shown that attractive people are more likely to be perceived as pleasant, are judged to be more socially competent, achieve better grades at school, are disciplined less and are more likely to be chosen for a job, and on average have higher incomes.

Mothers with more attractive babies talk to them more and maintain more eye contact. Babies respond more positively to pleasant faces.

proportion

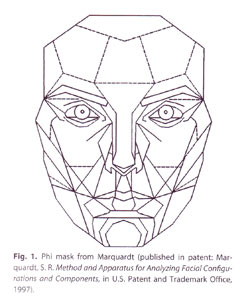

Artists and Plastic Surgeons have endeavored to calculate the dimensions of a perfect face.

The Fibonacci Mathematical Series and the Golden Mean, or Devine Proportion (1 : 1.618) which is derived from it, define the proportions seen in nature. An example of this is the beautiful nautilus spiral. A well proportioned human face and body also adheres to this ratio.

This proportion is fundamental to architecture and art. It defines, for example, the proportions of the Parthenon, da Vinci’s ‘Vitruvian Man’ and credit cards. This proportion defines the most generally pleasing shapes.

Research on stimulus and response has found that our mind is naturally attuned to find things constructed with the ‘Golden’ proportion pleasing to our eyes.

A so-called phi or beauty mask based on this proportion has been developed. This shows good correlation to subjective judgments. In practice for most aesthetic assessments the 1/3 : 1/3 rule works well.

Another facet of most plastic surgeon’s careers is some foreign aid work. For example Interplast Australia.

More complex cases need to be brought to Australia. Often this is through the Interplast or ROMAC organisations.

An example is Kim Chi Lee a burn victim from Vietnam:

Kim Chi’s home and family.

Nanise, another burn victim from Fiji. Nasal reconstruction:

artists & plastic surgery

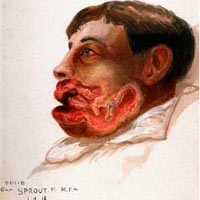

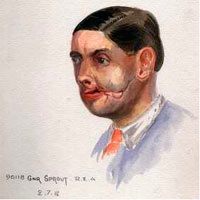

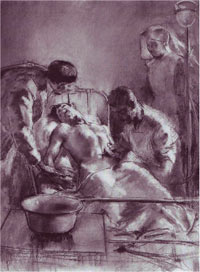

Probably the most well known association between an artist and plastic surgery is Henry Tonks and Sir Harold Gillies during World War I.

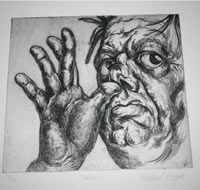

Henry Tonks, Self portrait and Saline Infusion

Henry Tonks (1862–1937) qualified as a surgeon, largely to please his parents. During his training he came into contact with ‘The Elephant Man’. He was a sensitive individual and a frustrated artist. He attended art classes and eventually gave up surgery to become a full time artist when offered Slade Professor of Fine Art at the Slade School in London.

When World War I broke out he volunteered for service as a surgeon. During this time he came across Rodin, who was at that time a French refugee.

Auguste Rodin, by Tonks (Tate Gallery, London)

During his war service he met Sir Harold Gillies and was fascinated by the work he was doing. He produced a series of, now famous pastels and paintings depicting the reconstruction of the faces of mutilated soldiers. (Now held in the Royal College of Surgeons and the War Museum.)

Tonks work and his dualistic personality in some ways mirrors the fusion of plastic surgery and art.

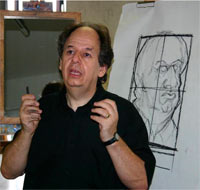

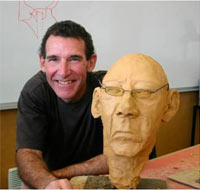

Michael Esson, Director, International Drawing Research Institute at The College of Fine Arts of The University of NSW is a modern day example of an association between an artist and Plastic Surgery.

Michael has an interest in human anatomy and surgery. He has sat in on courses run at The Royal College of Surgeons London to give Plastic Surgeons an introduction to drawing and sculpture and has also observed some plastic surgery procedures.

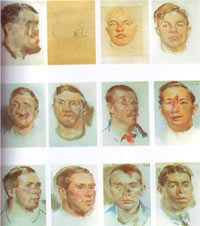

Back in Australia he has put together a similar course—‘The Art of Reconstruction’

Through a series of exercises including: clay modeling, drawing ( still life and life), and three dimensional cardboard skull fabrication Michael introduces different ways of thinking about form.

It has been clearly demonstrated to those who have attended, that as classically trained surgeons, we tend to flatten three-dimensional space as we do not move around the subject enough to fully appreciate the angles.

The lessons learned during this course have enhanced the quality of plastic surgery practice and, in many cases stimulated a broader interest in art.

surgeons as artists

Many plastic surgeons have high level artistic pursuits outside of medicine. For example:

- Accomplished glass, bronze and marble sculptors. (Burt Brent of ear reconstruction fame is internationally recognised for his animal bronzes)

- Published photographers

- Painters

- Collectors

- Musicians

- Winemakers

- Aesthetic Surgery

Examples of plastic surgeon’s art on the cover of a professional journal.

home | about | contact | top